All Hallows’ Eve and the Reformation’s Dawn

On November 1, All Saints’ Day on the Christian calendar, the Church remembers its martyrs and saints. This makes October 31 the Eve of All Saints, a.k.a. All Hallows’ Eve or Hallowe’en. The time of year for the remembrance of the saints was chosen in part to counter unchristian festivals which focused on spiritism, witchcraft, and the like. These practices flourished in much of Europe, spurred in late Autumn as pagans watched the lengthening of the night and the loss of daylight.

Much Halloween costuming and carousing has roots in practices of bygone ages. Stemming in part from Christian conflicts with pagan beliefs in parts of Europe, it included the mockery of Satan, intending to show that he had no power over Christ’s Church. Similarly, Martin Luther later said, “I often laugh at Satan, and there is nothing that makes him so angry as when I attack him to his face, and tell him that through God I am more than a match for him.”

Of course Christians — particularly “Protestants” and most especially Lutherans — have another reason to know this day. The Evangelical (Gospel) movement that became Lutheranism and the subsequent Reformation stirred on All Hallows’ Eve in 1517. Martin Luther knew that annually on All Saints’ Day his prince (Frederick III) displayed purported relics of the saints in Wittenberg, Saxony. The young theologian picked the customary bulletin board (the castle church’s doors) to post a series of topics for debate concerning errors he perceived in Roman Catholicism. Among these, Luther included the invocation and worship of saints in his challenge — practices that All Saints’ Day emphasized.

Of course Christians — particularly “Protestants” and most especially Lutherans — have another reason to know this day. The Evangelical (Gospel) movement that became Lutheranism and the subsequent Reformation stirred on All Hallows’ Eve in 1517. Martin Luther knew that annually on All Saints’ Day his prince (Frederick III) displayed purported relics of the saints in Wittenberg, Saxony. The young theologian picked the customary bulletin board (the castle church’s doors) to post a series of topics for debate concerning errors he perceived in Roman Catholicism. Among these, Luther included the invocation and worship of saints in his challenge — practices that All Saints’ Day emphasized.Luther wrote in Latin, thinking to keep the discussion among churchmen. However, opportunistic printers quickly translated and published these items in German, exposing Saxony and, later, all of Germany, to these issues. This religious debate was joined by increasing nationalism and enhanced by political and military considerations throughout Europe. The combination of factors triggered the spread of the Lutheran Reformation throughout Europe. In its wake, Roman Catholic domination of the continent crumbled, changing political and social boundaries. Most non-Roman Catholic churches in the West owe at least part of their existence to the Reformation and its aftermath.

Reformation Day is thus celebrated every 31 October as Lutherans mark the anniversary of the 1517 posting of the Ninety-five Theses. While divisions occasionally arose among Christ’s followers from the time of Jesus’ earthly life onward (see, for example, the conclusion of John 6), the Reformation marked one of the two great divisions in the Church. The other was the Great Schism, the split between the Eastern (Orthodox) and the Western (Roman Catholic) churches that grew for years until erupting in AD 1054.

While the Great Schism left each side relatively intact, the Reformation’s aftermath did much more to dissolve earthly unity. This was partially because of the times, with their Renaissance emphasis upon nationalism and freethinking. Luther and his associates were excommunicated by Rome and many political entities ranging from cities to large regions followed their religious leaders in this Evangelical reform movement.

While the Great Schism left each side relatively intact, the Reformation’s aftermath did much more to dissolve earthly unity. This was partially because of the times, with their Renaissance emphasis upon nationalism and freethinking. Luther and his associates were excommunicated by Rome and many political entities ranging from cities to large regions followed their religious leaders in this Evangelical reform movement.Often seeking gain political advantage and protection from organized persecution, others who disagreed with Rome but who did not agree with Luther joined the Lutherans for a time. Later, some of these splintered into other bodies. Meanwhile, although churchmen in England such as Robert Barnes agreed with Lutheran theology, their influence was blunted by other religious leaders as well as the social and political desires of King Henry VIII. Protected by water while continental Europe dissolved into ongoing squabbles, the English had a head start in establishing a state church independent of Rome. Yet as the Church of England spread, it continued moving farther from the Lutheranism that sparked it. This Anglican Church also showed an adaptability that would allow all manner of practice and a wide variety in teaching as the years went by.

Since it started with Luther — who built on the work of earlier theologians and reformers — the Lutheran Church traditionally emphasizes the day with more zeal than do most others. This can be positive, reminding us of the core reason why it all happened. Martin Luther was convinced that the saving Gospel of Jesus Christ was being obscured by legalism and empty, unchristian ceremonialism. Thus, when Christians gather to receive and rejoice in salvation by grace through faith in Christ, such celebrations are good.

True heirs of the Reformation hold pride only in the merits of Christ. Thus, when Lutherans (or others) use the day for empty boasting, bragging on Luther, or other errors, they a return to the legalistic bondage that the Reformation sought to cast off. They act contrary to the very Reformation they suppose themselves to be celebrating. Therefore, we abhor “Catholic bashing” and any other misguided and vicious attacks on other confessions. We also restrain sharp criticism of fellow Christians save over important matters of doctrine and practice.

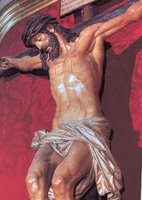

Misguided heirs to Luther do great harm when they throw out ceremonies and traditions that the reformers kept because they think of them as“too old-fashioned” or “too Catholic.” The Lutheran Reformation was intentionally non-radical. Luther urged the Church to hold on to practices that were not contrary to the Gospel and to remember, respect, and retain the customs of early Christianity. He desired the Evangelicals to keep crucifixes, religious statuary, stained glass windows, and the like but to use them as teaching tools rather than objects of veneration or worship.

Misguided heirs to Luther do great harm when they throw out ceremonies and traditions that the reformers kept because they think of them as“too old-fashioned” or “too Catholic.” The Lutheran Reformation was intentionally non-radical. Luther urged the Church to hold on to practices that were not contrary to the Gospel and to remember, respect, and retain the customs of early Christianity. He desired the Evangelicals to keep crucifixes, religious statuary, stained glass windows, and the like but to use them as teaching tools rather than objects of veneration or worship.The Lutherans kept vestments (pastoral clothing) and paraments (altar cloths and related material). They celebrated Communion “every Lord’s day” and on all the other major religious feasts (including All Saints’ Day). They retained individual confession and personal absolution by the pastors, throwing out only the practice of imposing penance upon those who confessed. In line with Scripture and Christian doctrine throughout previous centuries, they taught baptismal regeneration, the real body and blood presence of Christ in the Supper, and the need for formalized confessions of faith in order to buttress the truth and to rebuke and refute error.

Send email to Ask the Pastor.

Walter Snyder is the pastor of Holy Cross Lutheran Church, Emma, Missouri and coauthor of the book What Do Lutherans Believe.

Technorati Tags: Reformation | Reformation Day | Lutheran Reformation | Protestant Reformation | Martin Luther | Robert Barnes | Renaissance | humanism | Wittenberg | Germany | Saxony | history | Church Year | liturgical calendar | Christianity | Christian | Christian | Lutheranism | Lutheran | Evangelical | Protestant | Roman Catholic Church | Catholicism | Orthodoxy | Eastern Orthodox Church | Great Schism | festivals | theology | historical theology | Church history | Christian history | Saxon history | German history | European history | Ask the Pastor

Newspaper column #526

1 Comments:

Hello,please visit the new site www.martin-luther2017.de and http://katharinavonboraev.blogspot.com

Interesse Linkpartner?

Yours sincerely

Guenther Troege

K.-von Bora Association

Post a Comment

<< Home